|

| Does the investigator on the right just think this all is a bad black mold infestation? Too calm... |

Recently, a friend started a pandemic Call of Cthulhu campaign with me using a 1-on-1 set-up. The idea was that my Arkham city investigator, Henry Heart, PI (hat-tip to you Sam Spade & Joe Dimond), could easily be joined by any number of other characters should friends and family want to join us as they desired. The backbone of the campaign would be mostly short investigations and one-shot adventures.

CoC suggestion #1: CoC is very conducive to a one-player and one-GM set-up: combat light and friends can drop-in/-out.

CoC suggestion #2: DON'T BUY ANYTHING- grab some d10s and download the free quickstart rules which are FAR better than the player's handbook for CoC.

Now, I really wanted to stick to the basics of running an investigation. I wanted to actually try to work out suspects, locations, motives, and weapons to give to the cops instead of just jumping to, "Whelp no doubt this is the work of that old slimy bastard of the benthic zone-- Cthulhu!" Yes, I know most CoC stories end in just that revelation (of various colours), but maybe I could also just solve investigations by proving whoever the Arkham cops caught was innocent. Saves the trouble of convincing folks of magic.

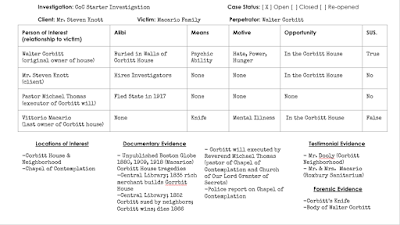

This reminded me of Sean McCoy's post on Failure Tolerated about investigations. I particularly enjoy the investigator's sheet he put together in his post and re-created my own in Google Slides. I also agree with Sean that doing actual investigating is where the fun of CoC lay.

For my 3rd investigation, I began using Sean's sheet (see below). This sheet has been pretty great both as a meta-game tool and an in-game object. That duality is what I think is so nifty- it works well in both contexts. This is not how I feel about the "quest log" in D&D which can be a handy tool for the players but feels weird from a character's in-world POV. The sheet also has been helpful in culling the many "can do" courses of action into "should do" actions. Also helpfully points out that while we might understand what is going on (or have a strong guess), we can only prove about half of it to the cops.

|

| Wish I had used one for the first 2 investigations |

|

| Investigation Sheet for The Haunting |

Now, sure, The Haunting is a decent starting adventure for teaching the players what to do mechanically in CoC. And perhaps the Keeper as well. However, it does not really help me understand how to build a good mystery. The players are told that their client, Mr. Knott, wants them to figure out what happened to the Macario family while living in the Corbitt house so he can clear the property of its bad reputation. The game instructs the players (literally via Handout #1) to seek information at the newspaper, library, and police department and Mr. & Mrs. Macario are in an asylum.

If the players jump to the Marcarios they will learn there is a "spirit" in the house. If they go through documentary evidence they will learn that Corbitt built the house, was sued by neighbors, died, and the will was carried out by Pastor Thomas who fled the state in 1917. Thomas is connected to a shady church that burned. So, there is really nothing to puzzle out except what's in the house- but would new characters be motivated to believe in the supernatural? The meta-logic of CoC is going to cause the players to think so, but why would the characters?

CoC suggestion #3: Anytime players immediately jump to a supernatural explanation out loud, in character or out, as a reason for X events, drop their Sanity by 1d2 representing the character slowing choosing the irrational over the rational; 1d8 if they agree to increase their Cthuhlu score by 1

The PCs could convince Mr. Knott that nothing is going to happen to anyone renting the house. Because all actual evidence points that way- the Macarios went mad and are now locked up. And the investigator sheet points to that too- no other characters have the means, motive, and opportunity outside of a supernatural explanation (Corbitt himself). Open and shut case. If players go to the Corbitt house they can find Walter Corbitt entombed and his murderous will still active. And THAT IS what is causing the problem. But players crawling around in a spooky location trying to find a wraith's tomb behind a secret wall, to me, becomes a D&D dungeon crawl more than a CoC investigation.

I might have not played enough, but I think interesting investigations in CoC would somehow:

- Create multiple likely perpetrators (What if you grab the wrong guy?)

- Have a possibility to close the case with non-supernatural evidence/events

(How do you convince people of magic without being accused of lunacy or worse yourself?) - Require rational reasons & evidence to convince the cops or authorities to take action

(Can't just drop a copy of De Vermis Mysteriis on the Police Chief's desk) - Save supernatural elements to creating lingering doubt, slow burn, and/or big reveals

(Was it really the husband or was he in fact possessed? And why have the killings not stopped?) - Have the ability to get the investigation wrong

(Person X has no alibi on the night of the murder but does have a motive and opportunity, but the investigators add a supernatural explanation as to the "means" but lack proof that it occurred)

For The Haunting I would keep the undead Corbitt as the true antagonist, but maybe change things:

- Vittorio Macario is innocent, but still had an earlier very heated dispute with his wife about her activities with the Chapel of Contemplation and her wanting to leave him w/ the children

- Pastor Thomas might be trying to gain control of the Corbitt House that is owned by Knott and suggested the property to Macario knowing what is there

- The Macario family would be new members of the Chapel of Contemplation creating further context and possible suspicion about their own activities

- Corbitt House is a legal fight for ownership between Thomas and Knott

- Have a 3rd party burn down the church, but for totally separate reasons unrelated to the case at hand

- Vitttorio's wife knows he's locked up but refuses to testify because she knows he wouldn't purposely do what he did and she's afraid for her safety since leaving town and the Chapel

- Provide some encounters of people looking to stop the investigators like rougher Chapel members not liking their snooping around

|

Vittorio has a stronger reason to be the actual perpetrator. The connection between the Chapel is made more ominous and deeper. Thomas and Knott have some personal hate, which calls into question why Knott is going with "independent investigators" (who might include former bootleggers or mob fixers). And Pastor Thomas also has more suspicious occult activities, but is still not the actual killer.